Retzer - Blood and soil

The resurgence of Blood and Soil: symbols and artefacts of Völkische Siedlungen and Neo-Nazi Villages in Germany

TERESA RETZER

This paper focuses on new Rechte Siedlungsbewegungen (movements of right-wing “settlers”) in Germany, whose historical origins partly lead back to the Völkische Bewegung (Völkisch movement) in the mid of the 19th century.[1] I will define several different types of Rechte Siedler (right-wing settlers) descending from the Alte Rechte (neo-Rightists) and the Neue Rechte (New Right), and investigate their history, ideologies and ways of living.[2]The Alte Rechte believes that Germany, according to its national law, language and culture, is identical to the Deutsche Reich (1933–1945) and refers positively to the National Socialist ideology. Their supporters glorify Hitler’s regime, and deny the holocaust and other war crimes of the Nazis.[3] In contrast, the Neue Rechte believes that modern-day Germany is a successor state of the Deutsche Reich and tries to employ new political concepts within this frame distinct from National Socialist ideology. Most of their supporters also deny a share in responsibility for the Nazi crimes.

Both Alte and Neue Rechte identify with the German Militarism Movement, but only members of the Alte Rechte can also be described as “neo-Nazis”.[4] Neo-Nazism can, in contrast to groups from the Neue Rechte, be defined as a counter culture that is practically based on their antithetical attitude towards the central beliefs of the political, societal and cultural landscape in Germany.[5] Their extremist ideology is mostly based on the repetition of historical far right ideas; relatedly, they deploy a diverse set of symbols and artefacts in their visual culture that refer to a variety of historical right-wing ideologies, revealing inconsistencies within their Weltanschauung (world view).

New Rightists, by contrast, engage critically with their ideology in order to create new ideas, which has been described as a “positive” rather than the neo-Nazis’ purely “negative” attitude. Right-wing intellectuals describe themselves as New Right in order to gain a positive image and they often support Völkische and youth movements of the New Right rather than radical neo-Nazi (youth) groups.

To be born in Germany means to inherit a collective memory of guilt, a condition that presents Germany—in my opinion—with opportunity rather than loss: instead of plunging into a self-pity that might destroy their national identity, many Germans gave up patriotism. In its place they generated a role that is internationally known for taking responsibility for the crimes of World War II and moreover, those people who are today exposed to war crimes, anti-Semitism, racism, euthanasia or homophobia. Angela Merkel had been heavily criticized by the German parliament and the general public for her welcoming attitude during the ‘refugee crisis’ in 2015, but instead of backpedaling she reminded her critics of the Third Reich when German intellectuals lived in exile. Nevertheless, the rise of the right-wing is a problem that Germany, as many others, is facing today. While radical neo-Nazis in urban areas get much attention from the instruments of the German state, Rechte Siedler can be disregarded more easily as they live secluded lifestyles and appear to be harmless.

The purpose of this study is to address the current rise of the Rechte Siedlungsbewegungen in Germany. This movement seeks to extend its communities over the whole of Germany, including the former states of the Germanische Reich throughout Europe. A short evaluation of the current state of right-wing groups in Germany and the analyses of the symbols and iconography different groups use will show some distinctions and also make clear that the most radical communities deceptively appear to be the least harmful.

The Völkisch, Siedlungen, (historical) Völkische Siedlungsbewegung, and Rechte Siedler today

The term völkisch is supposedly untranslatable. While the root Volk means “people,” the implications of völkisch are broader and profoundly ethnic in scope.[6] The Völkischen or the Völkisch people of past and present iterations are often identified as a splinter group of the supporters of National Socialism, and today they are often seen as neo-Nazis. But as much as the history of the Third Reich has managed to overshadow the pluralism of German nationalisms, in both, its ideologies and its organizations, the nationalism and ideology of the Völkischen cannot be reduced solely to the dogmas of the NS ideologues such as Walter Darré, Alfred Rosenberg, and—least of all—Adolf Hitler.

The ideologies of Völkische Siedler are built upon a newly organized conception that consists of old and new ideas and which manifests in their well-considered use of symbols and artefacts. While neo-Nazis are often uneducated people, many intellectuals can be found amongst the Völkische Siedler, who, moreover, expand their ideas by founding their own kindergartens and schools, publishing magazines (such as the Nordische Zeitung), and organizing symposia and internet platforms to distribute and also reflect on their ideologies.[7]

The term Siedlung (pl. Siedlungen) derives from the Old English word sedel which means abode or residence.[8] Since the industrialization of the early 19th century, with its high demand for factory workers, Siedlungen were planned settlements in rural and urban environments for worker families located close to the factories. Rechte and Völkische Siedlungen can be understood as networks of politically, and culturally like-minded people. The families living in a Völkische Siedlungsgemeinschaft (settlement community) are also called Sippen, which implies in part that they are biological relatives, but also suggests an ideological bond beyond a blood-relationship.[9] During the historical Völkische Bewegung of the 19th century and later in the Third Reich the Sippe became more important than the family for its political function to unify ideologically like-minded people. As such, it was one of the key words in the NS propaganda apparatus.

Blood, soil, and language were the foundational trinity on which the Völkischen built to reactivate the nationalism and social contract of the 19th and early 20th century. The historical Völkische Bewegung was grounded on the Deutsche Bewegung (1770–1830), a German Nationalist Movement leading back from philosopher, poet and theologian Johann Gottfried Herder to Romanticism, better described as a Weltanschauung than an ideology. The Völkische Bewegung was a central movement within the German Kulturnationalismus (Culture Nationalism) of the last three decades of the 19th century and became official with the foundation of a Völkische organization, the Deutschbund, in 1894.[10]

The Völkische Bewegung drew its fundamental beliefs from the principles of “alternative” doctrines such as alternative medicine, vegetarianism and naturism, and was influenced my occultism and Northern mythology. Before and during the Weimar Republic, Völkisch was not only a propaganda term but also reflected the identity crisis of the German people. To them, Völkisch expressed a xenophobic and traditionalist nostalgia based in folklore in order to glorify German’s prehistory. In addition to its spiritualist, populist, and rural-agrarian dimensions, Völkisch meant “racist” and by 1900, it also signified “anti-Semitic”.[11]

Since the early 1920s, under the influence of Hitler’s power politics, Walter Darré formed the premise of Germaneness rooted in a central place, the Deutsche Reich, a formation that resembled the idea of the ancient Roman Imperium rather than that of a nation-state as in France. Like other right-wing movements in the beginning of the 20th century, the Völkische Bewegung was absorbed by Nazis and its organizations, such as the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth) and the Schutzstaffel (SS).

However, the (re-)construction of an essentially mythical German past detached the Völkischen from Christian monotheism, and the Völkische Bewegung endeavored to reinvent a German, pagan religion. This tendency to build up a purely German society, politically, religiously and culturally strengthened was also the cornerstone for other nationalist reorientations in Europe after World War II and today, in divisions as varied as revolutionary nationalism, and neo-Nazism.[12]

The connectedness of the far right-wing in Germany: political parties, organizations, and Siedlungen

A short outline of the right-wing scene of Germany will show that Völkische Siedler and other sorts of inclusive right-wing spaces in particular—if in Germany, France, Switzerland, Austria, or Hungary—have to be taken seriously by the public and the European governments. Both Völkische Siedler and the inhabitants of neo-Nazi villages often support or are dedicated to right-wing progressive political parties, associations, public and private institutions, (extremist) activists from autonomous groups, or publishing houses.[13]

One of these most influential autonomous organizations from the New Right is the Identitären. The European prototype was founded in 2002 in France as the Mouvement national républicant. Austrian supporters founded their own public association in Austria; Germany followed in 2014 with the foundation of the Identitäre Bewegung. The Identitären in Germany are mostly active in the East; in the cities Halle and Leipzig in Saxony they have founded living communities and organize nationalist protests on Mondays. Another currently very active far right association is Pegida—Patriotische Europäer gegen die Islamisierung des Abendlandes (Patriotic Europeans against the Islamization of the West)—which originated in 2014 in Dresden. The members of many of these new autonomous groups are young and educated people; some of the founders of Identitären met while studying philosophy in Vienna.

Pegida, the Identitären, and many other radical groups from the New Right dissociate themselves from the political symbols and ideologies of the Nazis, such as the swastika and overt anti-Semitism. The public performances of these groups are much more professional and civilized than the ones from neo-Nazi groups like the Volksfront.[14] In the 1990s the most influential organizations of right-wing extremists were still strongly connected to neo-Nazism and anti-democratic youth scenes. The Volksfront, for example, emerged from Skinhead culture in the USA and Europe and used unmistakable symbols such as the swastika and the number 88 (standing for Heil Hitler, as the letter ‘H’ is the eighth in the alphabet). However, the demonstrations organized by the Identitären and Pegida nonetheless often result in harmful riots. Some of the speakers they invite are known for their anti-Islamic and racist hate speeches. Many members of Pegida or the Identitäre Bewegung have been imprisoned before, or are under active police investigation because of xenophobia, demagoguery, duress, defamation and/or physical or grievous assault.

Furthermore, political parties such as the Nationaldemokratische Partei Deutschlands (NPD) and the Alternative Für Deutschland (AFD), along with intellectuals and groups from the youth scene, have taken on the possibilities of the Internet and assert their presence within social networks in order to digitally distribute their ideologies.[15] Many Commissions of Inquiry appointed by the major political parties in the German Parliament, the Federal Court of Justice and independent research associations and universities are investigating these right-wing movements in Germany.

It is the project of both the Neue Rechte and the Alte Rechte to relativize the Nazi past, which they seek to disentangle from Germany’s fate for all time. While the Alte Rechte glorifies the Nazis, the Neue Rechte searches for a non-Nazi past from which to form a positive German identity that might serve as a moral foundation for the future. Instead, the Neue Rechte turns to alternative German traditions that seem to be embodied by the Conservative Revolution of the Weimar years and the aristocratic and military resistance to Hitler. While neo-Nazis (Alte Rechte) express their ideas quite explicitly by showing their affinity towards the NS-ideologies through paintings, symbols and open speech, Völkische and Neue Rechte Siedler propagate their ideology in a much subtler way; for instance, as parents socially engaged with the kindergarten and school of their children, as friendly neighbors, or even as social and pastoral workers.[16]

Rechte Siedlungen in East Germany: The neo-Nazi village Jamel

Compared to the West, the former GDR states are still underdeveloped. The public infrastructure, including urban planning and fire-optic communication hardware, is backward, the quality of public schools is often bad—especially in relation to the south—and many young people fall into the failed “modernization trap”.[17] There are not only more neo-Nazi (youth) groups active in the East but its stagnation is a fruitful area for other right-wing movements. It is as an ideal playground for the Völkischen.

As demonstrated by a map produced by the Amadeu Antonio Foundation, a human rights organization and initiative for civil society and democratic culture, sites across Germany have been appropriated by Rechte Siedler (fig. 1). Many of the sites in this collection of alleged Rechte and Völkische Siedlelungsprojekte (settlement projects) are in the countryside of the North-East, in the former GDR (fig. 2). In West Germany, the largest concentration of right-wing Siedlungen is in Lower Saxony.[18]

Figure 2. West Germany and the GDR. From M. H. Brooke, “The Foundation of West and East Germany,” Military Histories. Accessed January 29, 2019, http:s//www.militaryhistories.co.uk/berlin/germany. © M. H. Brooke.

One exclusive right-wing space is the village Jamel in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (fig 3).[19] The first rightists settled down there a few years after the reunification of Germany, in the early 1990s. Other than the spaces occupied by the Völkische Siedler, Jamel has not been a planned right-wing space.

Jamel is a rural place in the countryside that seems idyllic with its flanking lake, surrounded by farming fields. The people living in this small village—that only consists of 8 to 10 families—should not be classified as Neue Rechte but as neo-Nazis because they explicitly orient themselves to the ideology of the NS-Regime before and during World War II. Unlike the Neue Rechte movements and intellectuals that position themselves (predominantly) against the NS-crimes, the leadership of Jamel does not differentiate the ideologies of the village from the National Socialists. Flags and symbols that refer to the propaganda art, films and the ideology of the NS Regime, such as fascist and anti-Semitic messages, are showcased freely around the village.

Until last year, when entering the village, you would have passed a wall painting placed on a garage wall (fig. 4).In the center is written in simplified German type “Dorfgemeinschaft Jamel—frei–sozial–national” (“village community of Jamel—Free–Social–National”. To the left of the wall-text one sees an archetype of an Aryan family and to the right a way marker, indicating the distances to cities and towns such as Rostock, Königsberg and Breslau. “Free–Social–National” has been the title of an album by the German white power music band Nordmacht, a band that is connected to Blood and Honour, a right extremist music network from the neo-Nazi scene that exists since the 1980s and is active in many countries in Europe, especially in the United Kingdom and in Scandinavia. Blood and Honour organizes transnational concerts of white power bands and coordinates musicians—mostly playing rock music—to expand their racial and anti-semitic ideologies.[20] The network also published radical propaganda writings such as “The Way Forward” and “Field Manual” that plead for the recapture of the world by the white northern race. In Germany, the network has been banned since 2000.

Among the three cities that the way marker points to is Breslau—today the Polish city Wroclaw, having belonged to Poland since 1945. For many neo-Nazis, these places are used symbolically to commemorate the German victories in World War II. In 1944, Hitler declared Breslau a fortress to be defended at any cost. During the Siege or Battle of Breslau, the city was besieged by Russian troops during the last three months of the war. The sign pointing towards Breslau and the others cities should be understood as a provocation, claiming the rights of the German-national ownership of these cities.

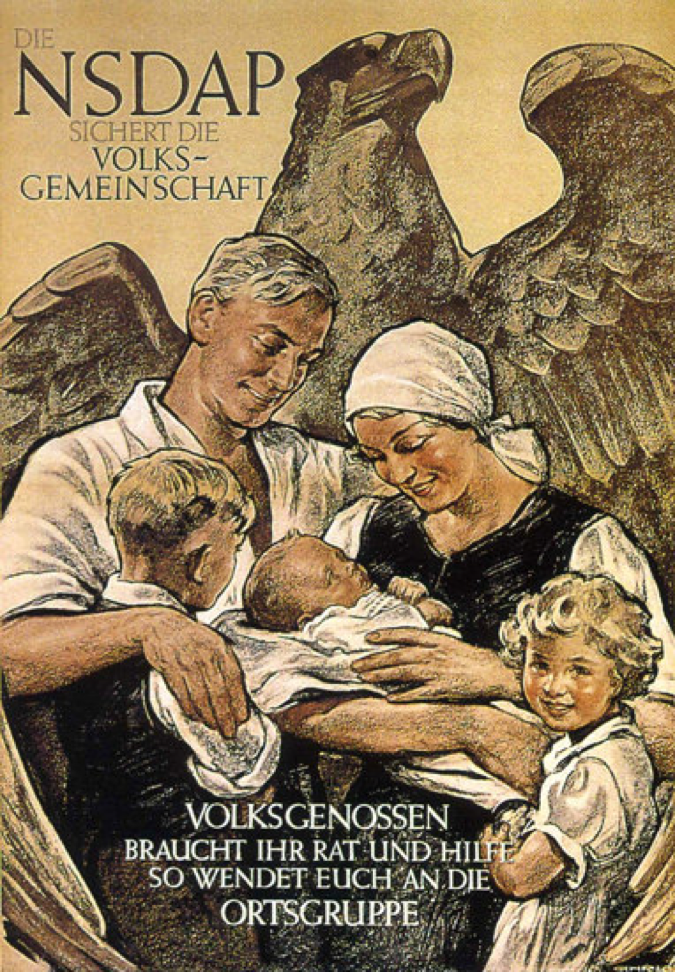

The composition of the family is clearly inherited from a propaganda poster produced by the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) in 1942 (fig. 5). The text of the propaganda poster reads, translated into English “The Nazi Party safeguards the people of the Nation” and “Fellow Countrymen! If you need advice and help then approach the NSDAP.”[21]

The message of the farming family has to be seen within the context of Blood and Soil propaganda of the NS-regime. While the blood would stand for a pure German and Northern ancestral lineage, the soil has not to be understood as a commodity serving for agriculture and the Lebensraum (living space) of the Volk (people).[22] This propaganda lauded the German peasant farmer as the salt of the earth, as the backbone of society. The simple life and the above average birth rate of small farmers were acclaimed as an example to urban citizens, who had been unrooted by industrialization.

The paintings of the Reichskünstler (artists of the Reich) Adolf Wissel and Hans Schmitz-Wiedenbrück show the special place of family and agriculture (figs. 6-7). Both NS art and ideology created romantic images of simple, hard-working, undemanding peasant folk nurturing large families who would work selflessly to feed the nation. While some NS-artists wanted to support the Nazi propaganda apparatus actively, others can be rather described as Völkische painters, who believed in conservative values other than the Nazi ideologies. Wissel had painted Völkische subjects already before 1933 and even if his work benefited from the NS regime he always rejected being a Nazi himself.

Within the Nazi propaganda apparatus farmers acquired particular significance because of the regime’s policy of self-sufficiency and autarky in food and other essential raw materials, an article of faith with some NSDAP leaders even before 1933. A particular cause of concern to conservatives of all kinds in the 1920s and 1930s, including NSDAP functionaries and peasants, was German society’s hunger for material possessions and dependence on foreign goods, especially those imported by the US. Many neo-Nazis and supporters of the Neue Rechte today boycott US-American franchise companies such as McDonalds or Starbucks, are against globalization, and often express an anti-cosmopolitan attitude.

Nevertheless, the Nazis’ “agrarian romantic” of the 1920’s and early 1930’s was contradictory to the actual infrastructural management that was employed by the NSDAP. They focused predominantly on the development of Hitlers Reichsstädte such as Berlin, Munich, Hamburg, Nürnberg and Linz. So instead of really pursuing the reruralization of Germany, the agrarian romantic has to be understood as a poltically constructed utopia.[23] In this time many people were dissatisfied with the effects of industrialization and large-scale urbanization and looked for alternative ways of life. The projections produced by the Blood and Soil ideology were designed to seduce people into approving Hitler’s expansionary strategy into the East, rather than establishing the realization of a farming society.

In the example of the painting in Jamel, we can see that feelings of dissatisfaction with the socio-economic situation in Germany have returned and these people are reactivating the Nazi nostalgia for an idealized rural past which had already been vanished back in the 1930s. Interestingly, the wall painting of Jamel was changed last year into an even more radical symbolic language (fig. 8).

The composition of this new version has become even more close to the NSDAP poster of 1942. The Imperial eagle or the heraldic eagle is holding the farming family like a bird’s nest symbolizing the imperial rule of the nation. The eagle has been used for the labeling of coat of arms of Germany since the second German Empire (from 1871 to 1918), and during the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) and the Third Reich (1933–1945). The eagle derives from the Roman Empire and has remained in use since 1945 also by the current Federal Republic of Germany, even though if the designation has changed into Federal Eagle.

Within these pictures—the NSDAP poster and the wall painting from 2017 in Jamel—the eagle should be seen as an imperial symbol depicting not only Germany as a shelter for an archetypal Aryan family but also as the visualization of the exclusion of “the Other,” non-Aryans or non-Germans. Therefore the imperial eagle symbolizes protectionism and shielding.

In the background of the new garage painting you can also see a group of farmers that is raising a wooden sculpture with ropes. This sculpture represents an Irminsul, the highest sacred relic of the Saxons, which was destroyed by the troops of Karl the Great in 772 (fig. 9).[24] One of the most important symbols of the pagan-German religion of the Germanen, the image is being instrumentalized here to promote the affinity of the inhabitants with German history. Hitler and his propaganda ministers had likewise made use of Germanic symbols such as the Irminsul or the Keltenkreuz (celtic cross) to mystify the history and to glorify the past of Germany. The symbol’s appearance in the new painting in Jamel could lead to the conclusion that the Siedlung has combined its neo-nationalistic values with other right-wing ideologies. The Irminsul is one of the central relics of the Völkische Siedler, which uses it, amongst other symbols, to illustrate their movement.[25]

Völkische Siedlerbewegung

Völkische Siedler can be described as a sect that is built on both old and new ideologies. The belief in a racial line of succession that is based on the Blood and Soil ideology was further developed by Walter Darré, who played a crucial role in the raise of Hitler between 1930 and 1933 by theorizing the ideal farming society of the National Socialists.[26] In his first book from 1930 Bauerntum als Lebensquell der Nordischen Rasse (Peasantry as the life-source of the Nordic Race), Darré argued for the restoration of Nordic Blood and the ancient tradition of the Germanentum (Germanic People) through the elimination of the weak and non-Germanic people. His text “Das Schwein als Kriterium für nordische Völker und Semiten” (“The Pig as criterion for the Northern Volk and Semites”) argued for fundamental differences between Aryans and Jews. While German farmers are characterized as brave and noble, he describes Jews as sponging nomads.

Both the historical and the current movements of Völkisch Siedler cannot simply be described as an Anti-Movement against the alleged dominant structures in Germany, like most right-wing movements throughout history. Rather they have to be taken seriously as a positivist movement, as they purport to provide solutions to prevent the ‘decline of the German state’. These Siedler look for spaces in the countryside to build a collective. Some of these settlements have existed for a long time as Sippen that have been active since the Weimar Republic. These Sippen are often intermixed with radical rightists and conservatives who do not necessarily share the extreme grade of their ideology but sympathize with the basic ideas of a Parallelgesellschaft (parallel society).

Today, Völkische Siedlungen can be found in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Netherlands, Russia, Poland, Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Norway. These Siedler are often rooted in the tradition of the Artamans, the leaders of the Germanic people in the early middle ages. In this way they recycle movements from earlier in the 20th century, such as the youth movement known as the Bund der Artamanen that was dedicated to finding true Volkstum (folkdom).[27]

The Irminsul symbol is often added to paintings, such as in Jamel, but mostly it is found in form of a stone sculpture, such as in the Siedlungen Koppelow and Klaber in Mecklenburg Pomerania (fig. 10).

The German philologist Ferndinand Haug has explained that the etymology of the term Irminsul derives from the word sul which comes close to the German word Säule (column).[28] The first part of the word, Irmin, cannot be conclusively clarified. Irmin is probably the enforcement of the second word and can be translated with adjectives such as strong, noble and great. The Irminsul has often been associated with the Northern god Irmin of the pagan religion of the German pre-Christian era. Today the Irminsul is being used as an anti-Christian symbol and is the key symbol of the Artamanenorden (Artaman community). The Artaman league was an agrarian and Völkisch movement that formed in the beginning of the 20th century and was dedicated to a Blood and Soil-inspired ruralism.[29] The name derived from the old German words “art” and “mahnen” meaning agriculture man. The primary insignia of the Artaman is traditionally rendered in gold on blue, with a figure that represents a plough pointing to the Northern star (fig. 11). The Artamans were active during the inter-war period, so the league became closely linked to, and eventually absorbed by the NSDAP in the 1920s.

The cover of the 2015 issue of the Völkische and Artaman magazine Nordische Zeitung centrally features a symbol of the Third Reich, the black sun (fig. 12); its design consists of twelve radial mirrore d sig runes, symbols employed as a logo by the Schutzstaffel.[30] It seems unusual that the neo-Artamans make use of this symbol which was rather created newly by Hitler instead of reflecting old Northern and Germanic ideologies. By contrast, an eagle holding a fish in his claws—which can be found in many Völkische publications and on their websites—is a symbol that fully reflects Völkische values; as it shows the supremacy of the Germanic eagle that symbolizes the pagan Northern religion of the Völkischen over the Christian fish.

The Völkische Siedlungen of Koppelow and Klaber, were founded partly by traditionalists during the industrialization in Germany in the mid-19th century and partly by Neuen Rechten that had left the city or other rural spaces in order to build up a community with Völkisch National values. These settlers first aim to change everyday life in the countryside, and as soon as the community becomes large enough these Siedler intend to expand their following. Nevertheless, experts such as Anna Schmidt, author of various books and texts about right-wing populism and extremism in Germany since 1945, posits that the primary danger of these right-wing Siedler is their isolated way of living and their subliminal means of recruiting other followers.

Figure 12. Cover of the Nordische Zeitung 3, no. 79 (2013). Accessed January 30, 2018., http:s//asatru.de/versand/main_bigware_29.php. © Asatru.de. Nordische Zeitung.

Conclusion

All over the world organizations, scientists, and politicians are looking for ways to enable the fight against right-wing extremism. In order to succeed in proceeding against anti-democracy, hatred and xenophobia we need to reveal the false constructions of their ideologies, especially of the New Right whose cultural and political purposes have not been widely investigated yet.

Siedler from the Neue and the Alte Rechte reinterpret the German and global history through their political ideology, they use special artefacts and symbols to visualise the bounding of their community—and hence produce narratives of their own beliefs. Both, neo-Nazis and Völkische Siedler, create large families living amongst village communities and associated neighbourhoods. When neo-Nazis settle down in villages amongst like-minded people or when they found new Rechte Siedlungen, they are not afraid to depict their affinity towards the National Socialists through outdoor paintings, sculptures and other symbols. Völkische Siedler, in contrast, may seem from the outside to be harmless, but their radical beliefs turn out to be just as racist, xenophobic and anti-Semitic, as those of radical neo-Nazis and more extremist youth groups of the Neue Rechte.

While the Völkische Siedlungsbewegung historically belong to a revolutionary conservative movement that is an alternative to the radical-conservatism of National Socialist ideologies, other Rechte Siedlungen remain strongly connected to Nazi beliefs. The different types of Siedler share some concepts in their ideologies, but it is the way in which they cultivate their ideas, the representational strategies, and the symbols they use to visualize and promote their beliefs that distinguish them most.

“Never ever again” is a well-known phrase accounting for Germany’s national heritage of shame. However instead of hoping for its affirmation, we need to face the problem of ideologically-driven collective memories as a real danger taking place in the present and confront rather than avoid spaces already occupied by right-wing extremists.

Teresa Retzer studied art history and philosophy in Vienna, Siena, Zurich, and Basel. Since 2017, she has concentrated on contemporary right-wing extremist subcultures in the former East Germany. Her developing PhD project investigates the interconnected relationship of contemporary art, society, politics, media theory and critical historiography. You can follow her work at teresaretzer.com.

NOTES

[1] This essay is related to my research topic “Right-wing spaces—Right-wing activism in Germany building up its own collective memory beginning with the occupation of architecture,” that has been presented at the Conference “Flags, Identity, Memory” (Lille, February 2018). My interest in contemporary Right Movements in Germany derives from the project “Rechte Räume (Right-wing Spaces),” organized by Professor Stephan Trüby, who teaches architecture and urban theory at the Technical University of Munich and coined the term.

[2] The literal translation of Alte Rechte as “Old Right” is misleading, as it might refer to the Old Right Movements in the United States which have a different historical background than the neo-rightists in Germany.

[3] Richard Stöss, “Rechtsextremismus im vereinten Deutschland,” in Polit-Lexikon, ed. Everhard Holtmann, 3rd ed. (Munich: Oldenbourg, 2000), 573.

[4] The German Militarism Movement begun in the Kingdom of Prussia in the 19th century as a consequence of the French invasions. Militarists believe that only a strong military ensures national autonomy following the law of the strongest that also equips military states to expand geographically, influentially and culturally. German Militarism only came to an end after World War II.

[5] Stephan Trüby, “Right-Wing Spaces,” e-flux Architecture: Superhumanity (January 2017), https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/superhumanity/68711/right-wing-spaces/.

[6] Jean-Yves Camus and Nicolas Lebourg, Far-Right Politics in Europe, trans. Jane Marie Todd (Cambridge Massachusetts/ London: Harvard University Press, 2017), 17. Völkisch was, by the beginning of the modern era, a loan translation from the term poularis to describe the simple, uneducated people (Volk), who did not Latin but rather the language of the people (Volkssprache) and did not belong to the medieval educated middle-class and the ruling elite. The philosopher of German Idealism, Johann Gottlieb Fichte used the term völkisch already in 1811 as a synonym for German in order to differentiate German-specific cultural and linguistic characteristics from the other people of Europe. See Uwe Puscher, Die völkische Bewegung im wilhelminischen Kaiserreich. Sprache. Rasse. Religion (Bonn: VG Bild-Kunst 2001), 29.

[7] Anna Schmidt, Völkische Siedler/innen im ländlichen Raum (Berlin: Amadeu Antonio Stiftung 2014), 14.

[8] Dr. Phil. Habil. Paul Grebe, ed., Duden. Etymologie (Mannheim: Dudenverlag, 2007), 643. Today the word Siedlung is being used to describe a group of similar mostly small houses at a city’s or town’s outskirts or in rural areas.

[9] Sippe describes the blood-relationship within a family, on which their patriarchal structure is based on. The patriarchy was the dominating societal system of the Germanic culture and politics which had emerged again in the age of European Enlightenment in the 18th century. See Grebe, Duden. Etymologie, 659.

[10] Stefan Breuer, Die Völkischen in Deutschland (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2008), 26.

[11] While they were long understood as one single movement, the Völkische Bewegung and Anti-Semitism are now being describes as separate historical movements that merged at the end of the 19th century. Even though the Völkische today are not necessarily also Anti-Semites, its majority is. Stefan Breuer, Die Völkische Bewegung in Deutschland. Kaiserreich und Republik (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2008), 32–33.

[12] Camus and Lebourg, Far-Right Politics, 17.

[13] Roger Woods, Germany’s New Right as Culture and Politics (New York: Palgrave Mcmillan, 2017), 1–3.

[14] Jörg Michael Dostal, “The Pegida Movement and German Political Culture: Is Right-Wing Populism Here to Stay?,” The Political Quaterly 86, no. 4 (2015), 523–531.

[15] It is also important to notice that the Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU) that is forming a coalition with the Angela Merkel-led CDU shifted to the right and some members of the Bavarian parliament even to the far right which has to be traced back to the ‘refugee crisis’ in Germany and the federal national interests of the free state Bavaria.

[16] Schmidt, Völkische Siedler/innen, 13.

[17] Lukáš Novotný, “Right-Wing Extremism and No-Go Areas in Germany,” Sociologický Časopis / Czech Sociological Review 45, no. 3 (June 2009), 596–7.

[18] Falk Nowak, Die letzten von gestern, die erstne von Morgen? Völkischer Rechtsextremismus in Niedersachsen (Berlin: Amadeu Antonio Stiftung 2017), 4.

[19] Jamel has stood in the focus of other far-right investigations and of the Federal Ministry of Justice for years already. Christian Bangel, “In Jamel-Deutschland,” Zeit-Online (August 13, 2015), accessed on January 30, 2019, https://www.zeit.de/gesellschaft/zeitgeschehen/2015-08/jamel-nazis-kommentar. The Amadeu Antonio Stifung for many years has supported the music festival “Jamel rockt den Föster” that takes place every summer in Jamel. It was initiated by two artists living in Jamel to offer resistance against the rightist people in the village. See Amadeu Antonio Stifung, “Übersicht der geförderten Projekte und unterstützten Personen 2018,” accessed on January 30, 2019, https://www.amadeu-antonio-stiftung.de/projektfoerderung/bilanz/.

[20] Romano Sposito, “Einstiegsdroge Musik,” Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (April 2007), accessed on January 30, 2019, http:s//www.bpb.de/politik/extremismus/rechtsextremismus/41758/einstiegsdroge-musik.

[21] “Die NSDAP sichert die Volksgemenschaft. Volksgenossen braucht ihr rat und hilfe so wendet euch an die Orstgruppe.” Translation by the author.

[22] Ben Kiernan, Blood and Soil. A Word History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur (Yale: University Press, 2007), 427.

[23] Kiernan, Blood and Soil, 454.

[24] Ernst Wagner and Ferdinand Haug, “Die Irminsul,” Fundstätten und Funde aus vorgeschichtlicher, römischer und alamannisch-fränkischer Zeit im Grossherzogtum Baden (Tübingen: Mohr 1908), 70.

[25] Schmidt, Völkische Siedler/innen, 22.

[26] Gustavo Corni, “Blut- und Bodenideologie,” in Handbuch des Antisemitismus. Judenfeinschaft in Geschichte und Gegenwart, vol. 3 Begriffe, Theorien, Ideologien, ed. Wolfgang Benz, (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter 2010), 45–46.

[27] Corni, “Blut- und Bodenideologie,” 45.

[28] Wagner and Haug, “Die Irminsul,” 71.

[29] Anna Bramwell, Blood and Soil. Walther Darré & Hitler’s ‘Green Party’ (London: Kensal Press, 1985), 101.

[30] Schmidt, Völkische Siedler/innen, 14.